Sometimes I have bad days, or even weeks. Over the past few years, these bad days have manifested for me in two opposing and yet integrated ways. The first is a deep longing for solitude, a desire to find some far off place away from people and the world, somewhere I don't have to interact with or perform for anyone. The second is a strong feeling of disconnect from the people around me, bringing on a sense of loneliness that seeps through even in a crowded room and carrying with it the belief that no one would notice if I was gone.

So many people experience such things. Depression, sorrow, and anxiety can feel like being lost at sea, floating on desperate dark emotions with no sign of land or refuge in sight. Sea of Solitude, a game developed by Jo-Mei Games, powerfully expresses these experiences through the exploration and healing of its watery world.

“Sea of Solitude is the most personal game I’ve ever made so far. I started writing it when I felt the loneliest, in both my private and working life,” Cornelia Geppert, writer, game design, and art director for Sea of Solitude, in an interview with Venture Beat. “I needed to let that out. It was really bursting out of me. I started writing down the first lines of the story, and the result is all this you see here, the game. But it’s not completely my thing, of course. It’s a team effort. Everyone who’s worked on it contributed.”

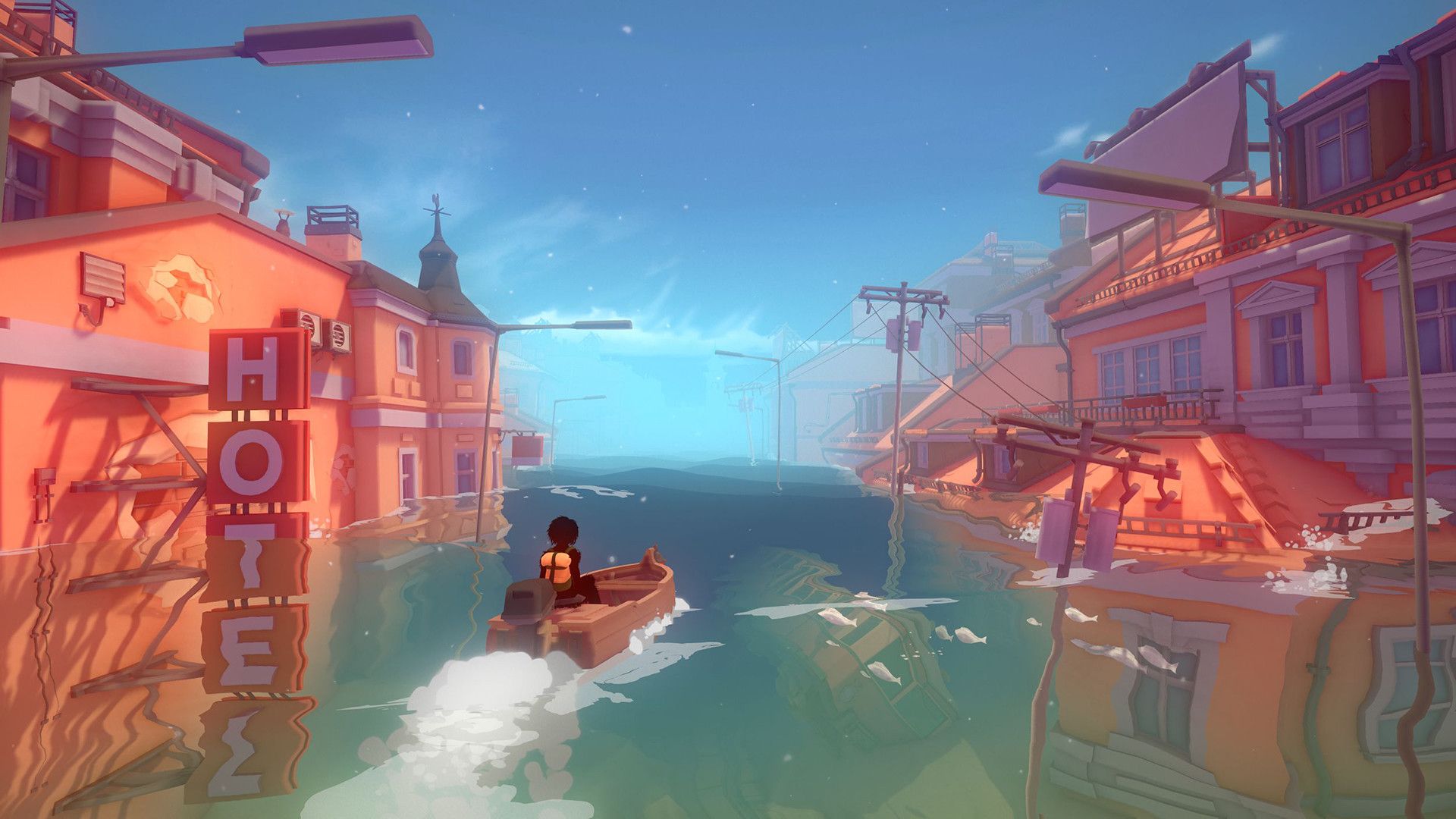

From the game's first moment, the artwork is beautifully dreamlike. Kay, a young shadowy woman, wakes in a boat in the middle of stormy waters and no memory of how she got there. Dilapidated buildings rise up like cliffs around her, with the rest of the city submerged underneath the waters — a world laid waste by the sea.

Monsters swim through these waters, stalking her or blocking her path. These monsters confront her, try to consume her, or flee from her. Whether semblances of herself or her loved ones, these creatures are representative of the ways in which mental health issues (loneliness, hopelessness, depression, anger, sadness, and so on) can make us feel monstrous. Even Kay herself is aligned with this monstrousness, a dark creature with bright glowing red eyes.

But as she travels these dark seas, Kay discovers pockets of light and healing. A lantern hanging on the bow of her boat forms a bubble of protective space around her, transforming the world from something bleak, stormy, and nightmarish into vibrant, pastel-infused daylight. The buildings that surround her are suddenly restored, polished, and new, the wreckage of the storm wiped clean, even if much of the city remains underwater.

As Kay moves from shadow to light and back again, trying to heal the world, the player witnesses how her perspective shifts based on her mental state. Sometimes the storms consume all, and at other times they recede, revealing the depths of the city hidden under the water, like a memory returning to the surface.

In fact, the entire game takes place within the same few city blocks, buildings, and structures — each of which feel entirely different depending on how deep the waters or whether the place is approached in daylight or storm. A street market, which the player previously explored in joyous daylight, may be frozen over with loss when it is returned to later. It’s a brilliant and beautiful use of structural storytelling, reflecting the ways in which a place can change in our memory, depending on our perspective at the time.

One of the many powerful elements of this game is how Kay works to cleanse the world of shadows, healing some of the monsters around her and trying to destroy others. In the darkness, she finds dancing orbs of light to guide her. When these light orbs are attached attacked by swirling shadows, she must work to remove the shadows, drawing them away from the orbs and trapping them within her bright orange backpack. By clearing away these shadows, she is able to return those she loves and the world to the light. Though, she can't quite seem to get there herself.

For all the work Kay does to remove the shadows and return the world to the light, she herself remains monstrous, a silhouetted figure against the bright colors of the cleansed world. The more shadows she clears away, the more she finds herself burdened, the backpack she carried growing larger and more cumbersome.

This was a part of the game that I connected to most deeply. Seeing the backpack become so heavy that Kay almost struggles to move is a powerful visual. In healing others, she fails to address her own needs — and while playing, I found myself wondering how often I do the same, spending energy supporting others around me and carrying their emotional burdens while ignoring my own feelings. What would happen if I let all that go? Would it be possible to still support others while also supporting my own mental health needs?

Sea of Solitude is not intended to be therapy (as the developers point out at the start of the game). However, it does directly address addresses heavy topics of mental health and personal healing through a beautiful and deeply emotional journey.

Thought the game is not subtle in its analogies, I found the experience to be both enlightening and cathartic. A game is not going to fix me or stop me from having bad days. But it can remind me that, even though I might sometimes feel lost, lonely, and monstrous, I am not alone. Whether meditation, therapy, friendship, exercise, or some other means, I have the power to find my own pathways out of the dark.